Three things that gave me clarity on Gendlin’s Focusing Book

When I created my 101 Workshop and Focusing for Beginners course, I re-read Eugene Gendlin’s classic Focusing book. It’s such a good read, and I enjoyed his examples. I use many quotes from the book in my teaching as so much is articulated so well!

Yet, there were a few things I was surprised by. The one that I disagreed with, and will not address in depth in this blog, is how Gendlin deals with the critic. I far prefer David Rome’s suggestions on Befriending the Inner Critic, which he in turned learned from Ann Weiser Cornell and Barbara McGavin.

And then there were three things that I found unclear. These were related to three points that I had received clarity on or found better explained in other resources, including other works of Gendlin or other Focusing teachers, or broader experts (a physicist!). So here are my three learnings about Focusing that came from other sources and might be helpful to you if most of your Focusing learning has been in reading the Focusing book:

What is a Handle?

In the Focusing book, Gendlin refers to the handle as “a word, a phrase, or an image [that comes] up from the felt sense itself” (p. 50) Others like Laury Rappaport add gesture or sound to the list. But where does the word handle come from? In his 1996 book Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy: A Manual of the Experiential Method Gendlin says on page 48 that “as with the handle of a suitcase, which brings with it the whole weight of the suitcase, the whole weight of the felt sense is brought forward by that one word or phrase when one repeats it to oneself.”

So a handle is like a headline that captures the main message of the felt sense. In the Focusing book, Gendlin uses the words “core”, “crux of all that” and “essence” (see page 64) to further point to what a handle brings. I like knowing that it comes from a suitcase however… this helps me understand the meaning of the word. Prior to prompting the handle step, he also instructs to sense all of that. So I’ve come to understood the handle to be a quite specific symbol. Something that captures what the whole of it is all about, rather than describing elements.

From this perspective, I would say that some of his handle examples can be confusing. When I teach about the felt sense, there are many ways that we can describe its physical sensations. Typically this includes location in the body, shape or size of the felt sense, and qualities of movement, density, texture, temperature and/or colour.

The handle examples of jumpy or burdened on page 63 are excellent in my mind. I can see how they can capture the quality of a felt sense as a whole. However some of the other ones could be aspects of something larger: sticky feels like a texture of something; heavy could be the weight; tight might be some sort of movement, like a pulsing. In these instances, I feel like these words might actually be descriptions of the felt sense, and the handle would be something else that captures its meaning.

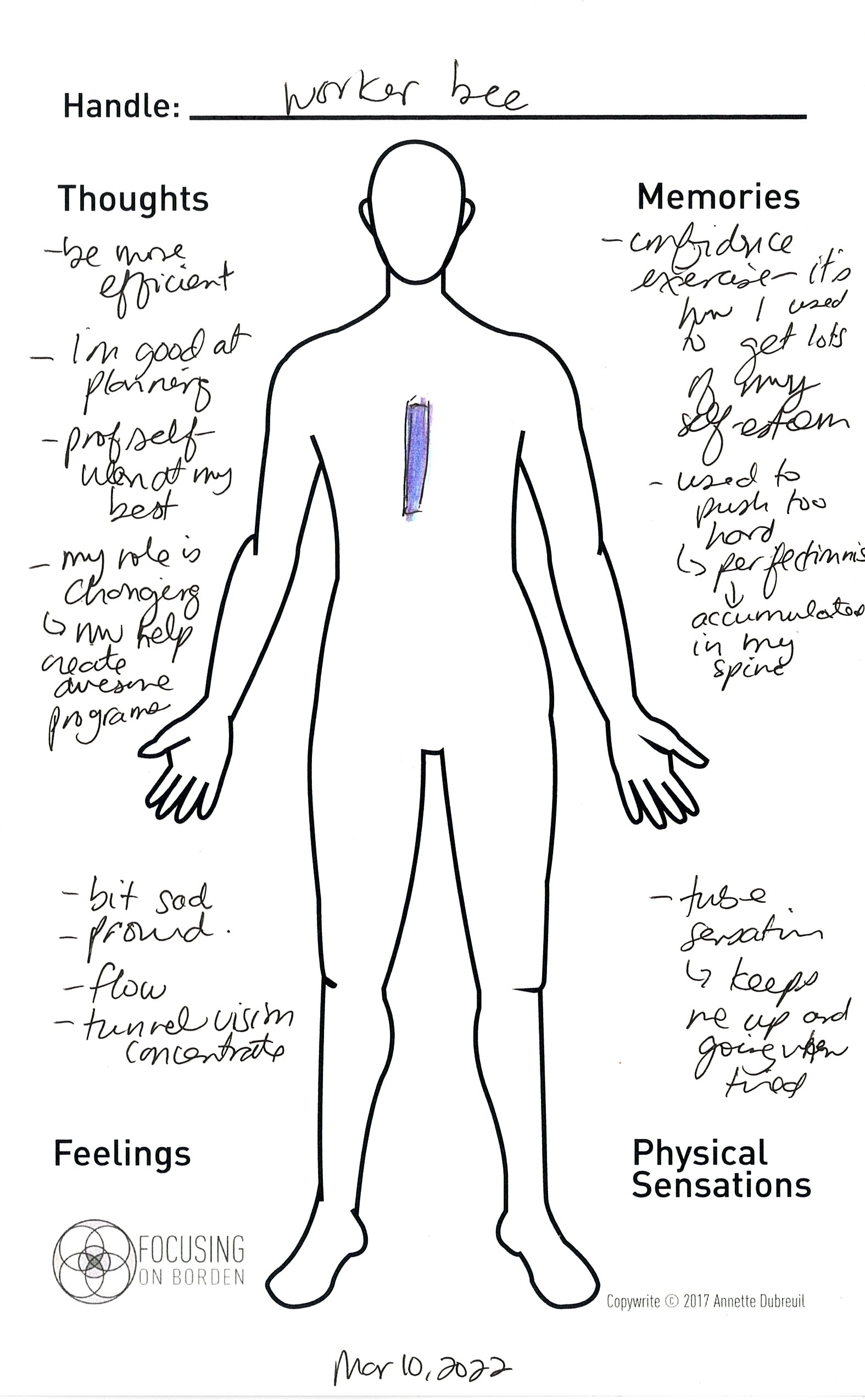

An example is a recurring felt sense that I’ve had of a metal tube in my chest area that comes with a tired feeling. Knowing it was metallic feeling and a tube shape didn’t shift this felt sense The shift happened after I got a handle for it as being a support rod that “keeps me up and going when tired”, like that would keep a mannequin up, so that I don’t collapse. I now recognize this felt sense as my “worker bee” part that can keep me going when other parts are exhausted..

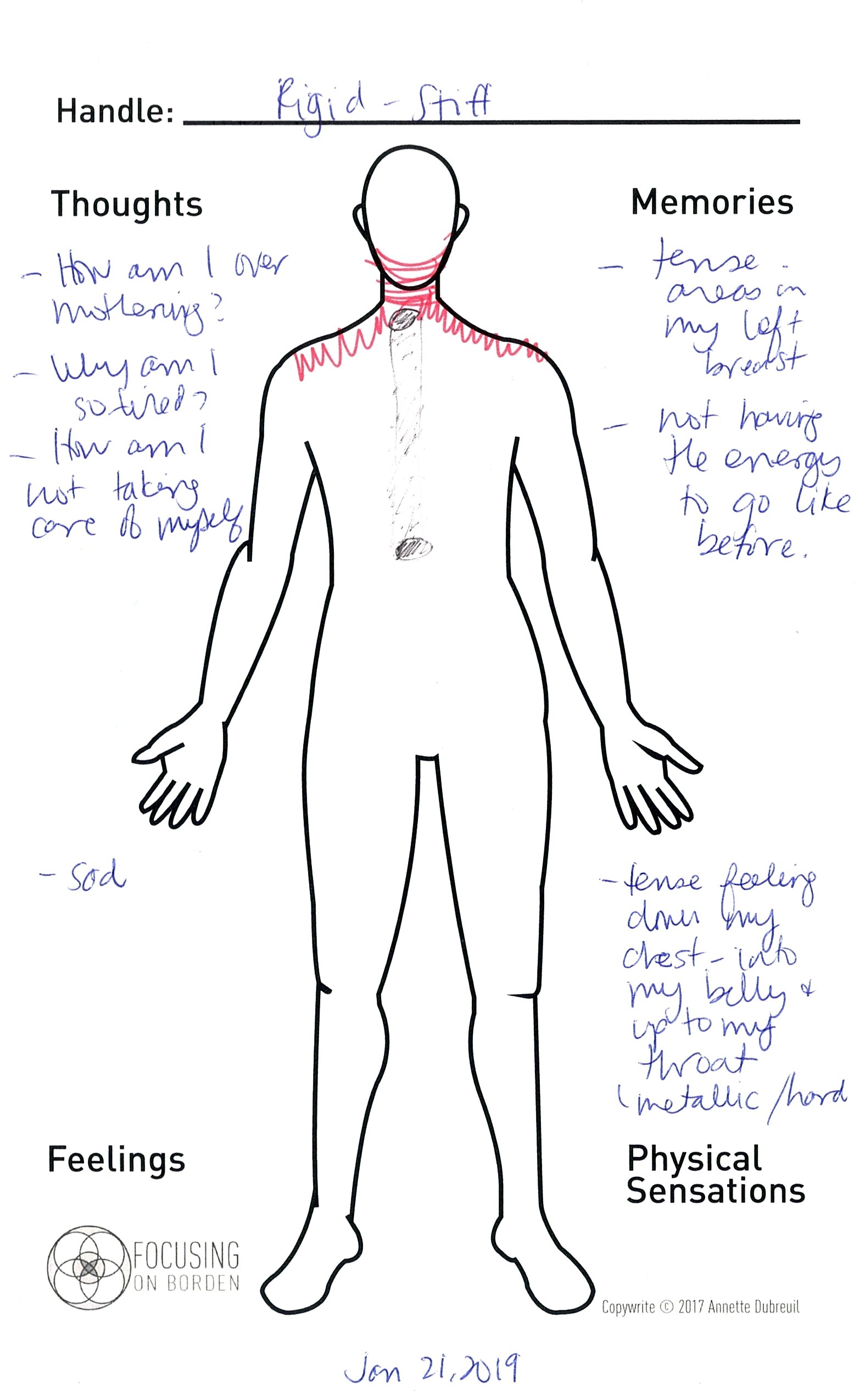

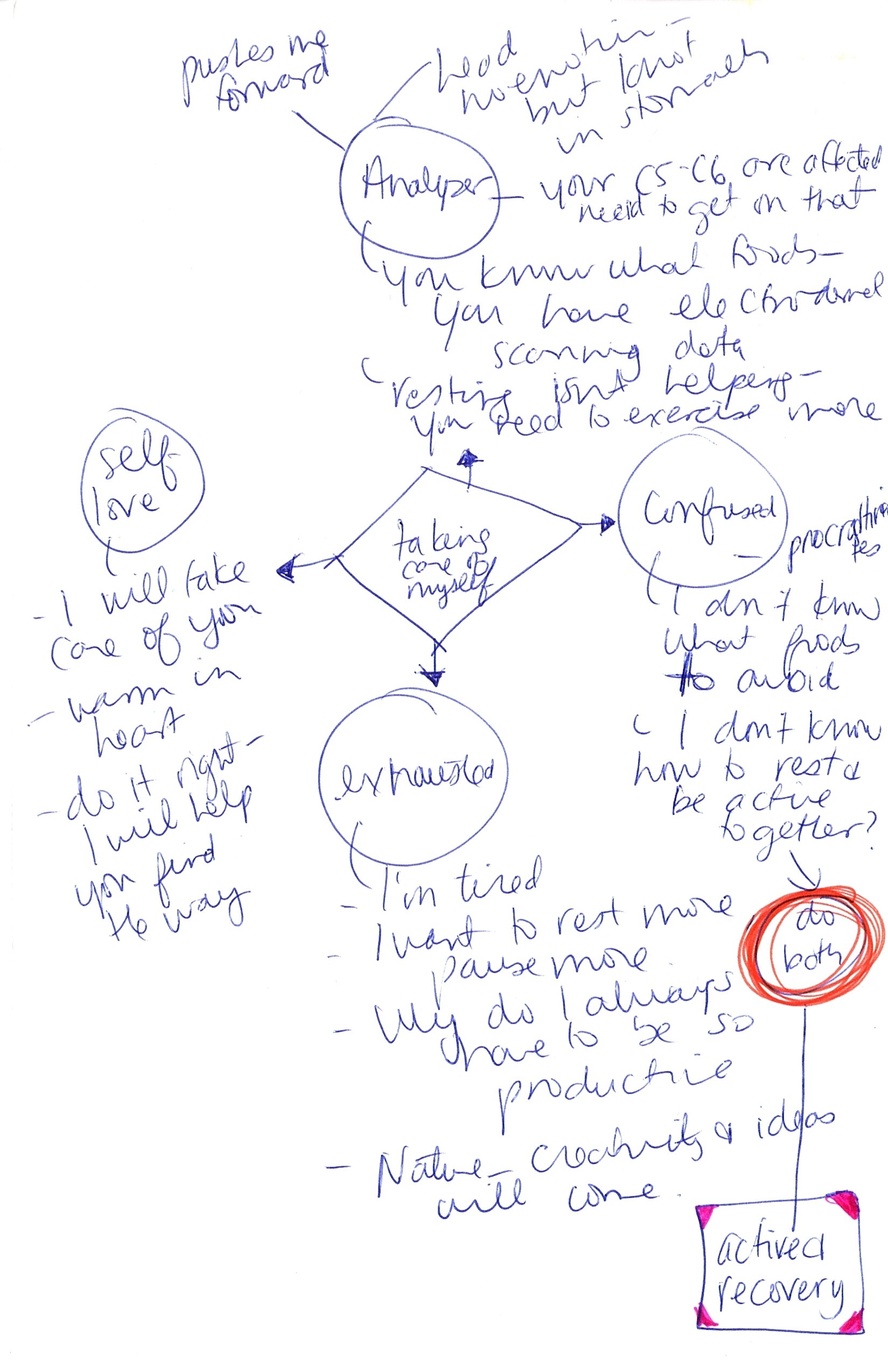

A 2019 card (front and back, see ones on the right), show a similar metallic feeling in my chest. At the time, I knew that this felt sense went with a feeling of not taking care of myself. A kind of mind map on the back of the card even notices that there’s something that “pushes me forward” but at the time it was conflated with another part of me, and I can now see there is a part that pushes and the part that helps implement. I didn’t know that the metallic tube sensation was the activation of this worker bee part that allows work to keep going.

My recent parts work seems to be revealing information about these subtle sensations that often have a fold or dorsal vagal quality. And getting the meaning by having a handle that captures the whole of what the felt sense is saying is what creates the shift. Which brings me to my next learning.

How do we get a Felt Shift?

Gendlin talks a lot about felt shifts, or body shifts as he calls them more often, in the book. He talks about what they feel and sound like (p. 45), how they can take time to come (p. 66) , and how we can create space for them (p. 118). That the “body shift, the changing in a felt sense, is the heart of the [Focusing] process (p. 29).”

As well, he explains how they “may come at any time during any of the focusing movements (p. 73).” For example, “you might have gotten such a shift and change in the problem already, when you sat quietly with the felt sense […] Or it might have come along with a handle word or image. It might have come while you resonated the handle with the felt sense.” (p. 66) But more usually we get “only a small” (p. 64) or “little tiny bit” (p. 66) of a shift of rightness in the earlier steps, and that bigger ones come later in step five/Asking.

But then Gendlin goes on to say that the body shift is “mysterious… we do not control when a shift comes. (That is “grace.”)” And while it is true we don’t control it… we can certainly explain how they happen more so than the above.

When I read a line in Ginny Whitelaw’s book Resonate: Zen and the Way of Making a Difference, I understood how felt shifts happen in a different way. Ginny says:

“Resonance is how energy changes form. And since everything is a form of energy, it’s how change happens. It’s universal.” –Ginny Whitelaw, physicist and Zen master, author of Resonate: Zen and the Way of Making a Difference

What I understand now is that a felt shift happens when the felt sense and symbol or meaning coming up resonate together. The symbol or meaning can include handles, but also a string of thoughts, or a memory, or a new connection. In other words when the felt sense and its symbol’s energy match or have the same vibration, that’s when felt shifts happen. Gendlin says this indirectly with the following quotes:

While explaining how to find a handle that captures the felt sense, he says “you are looking for: something that comes along with a body shift”. (p. 63)

In Resonating (4th step): “Let both sides—the feeling and the words—do whatever they do, until they match just right.” and “There should be a felt response, some deep breath inside, some felt release again, letting you know that the words are right.” (p. 65)

“The words and images that flow out of a feeling, by contrast, are the kind that make a freshly felt difference. They are the kind that make you say, “Hey! Hey, yeah, that’s what it’s all about!” These are the words and pictures that produce a body shift.” (p. 68)

“Along with the physical felt shift, something comes in words or felt understanding, which explains the trouble much more clearly, and usually in new terms.” (p. 78)

Now Gendlin wrote his thesis on related work, published as Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning: A Philosophical and Psychological Approach to the Subjective. It includes a chapter on seven ways that felt meanings function together with symbols. So I don’t mean to imply he didn’t know this, but rather doesn’t say it clearly in the Focusing book.

[June 2023 update: I have since been reminded that Gendlin discusses this topic in his paper A Theory of Personality Change (1964). There he says “Thus, to explicate is to carry forward a bodily felt process. Implicit meanings are incomplete. They are not hidden conceptual units. They are not the same in nature as explicitly known meanings. There is no equation possible between implicit meanings and "their" explicit symbolization. Rather than an equation, there is an interaction between felt experiencing and symbols (or events).” In plain language, I believe this means that when the felt sense and the emerged symbol interact, move each other (resonate), that the felt shift happens (the carrying forward).]

In short, I now think of the fourth movement, resonating, as a broader step to check the symbolization or meaning that is coming forward against the felt sense, not simply handles. And know that when the felt sense and a symbol has matched or resonated, at least implicitly, that’s when I see felt shifts happening.

What is the Focusing Attitude?

Gendlin powerfully says:

Whatever comes in focusing will never overwhelm you if you can have the attitude we call “receiving.” You welcome anything that comes with a body shift, but you stay a little distance from it. You are not in it, but next to it. […] You sense that there is space between it and you. You are here, it is there. You have it, you are not it.”—Eugene Gendlin, Focusing, page. 70-71.

The term “focusing attitude” however, isn’t used in Gendlin’s Focusing book. Rather, he says “Whatever comes in focusing, welcome it.” on page 69 in describing his sixth movement: receiving. Yet, I’ve come to understand the focusing attitude as a key piece in the work of Focusing. So I dug into its roots.

In personal communication with Mia Leijssen (2022), she shared that she and Jim Iberg co-created the term focusing attitude during their interactions, including University workshops, held in the years 1977-1984. She articulate the importance of the focusing attitude in her Focusing Microprocesses chapter, which you can view reprinted on the TIFI website from the Handbook of Experiential Psychotherapy where it was originally published. There, she references Iberg 1981 and says:

Focusing is characterised by, and can be distinguished from other activities by two aspects: the specific object of attention being the felt sense and the attitude adopted by client and therapist being the focusing attitude (Iberg 1981). —Mia Leijssen, 1998

So how else can we understand the focusing attitude? Leijssen describes it as “an attitude of waiting, of quietly and friendly remaining present with the not yet speakable, being receptive to the not yet formed.” Laury Rappaport outlines the following four key components of the focusing attitude: “welcoming; being friendly to; keeping company with; friendly curiosity” (p. 27). In my focusing training with Jan Winhall, we would often use the word nonjudgmental.

Focusing attitudes have been researched and measured with the Focusing Manner Scale, and many studies “have shown positive correlations or causal relationships between focusing attitudes and holistic wellbeing (Aoki and Ikemi, 2014).”

So if you hang around Focusers who use the term focusing attitude, that’s some of its history that you don’t find in the book that was published around the time the term emerged.

What are your insights?

Now I invite you to share your insights on Focusing practice. Add them to the comments below!

This is part one of a two-part blog series. Read the next blog, where I explore the use of self-compassion in the Focusing Attitude.